Ivca Vostrovska

Nature does nothing in vain, and more is in vain, when less will serve; for Nature is pleased with simplicity, and affects not the pomp of superfluous causes — Isaac Newton

Wabi-sabi is a difficult concept to grasp. The words “wabi” and “sabi” don’t translate easily. “Wabi” originally meant the loneliness of living in nature. More recently, it is used to describe a rustic simplicity or quietness that can emanate from an object – whether natural or man-made. “Sabi” is the beauty or serenity that comes with age, when the life of the object is visible in its wear and tear. Together, “wabi-sabi” can be understood as raw beauty or flawed beauty.

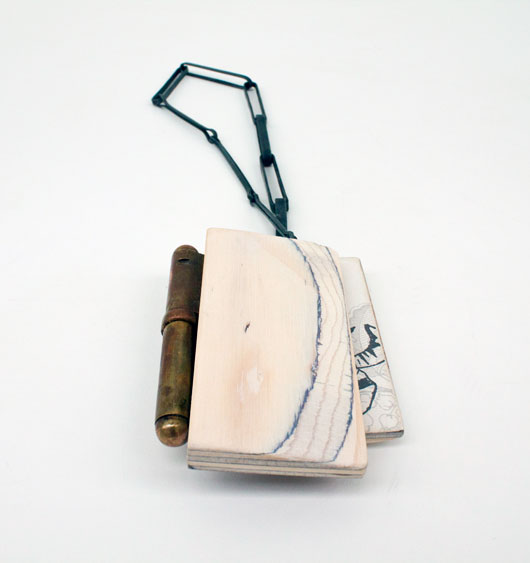

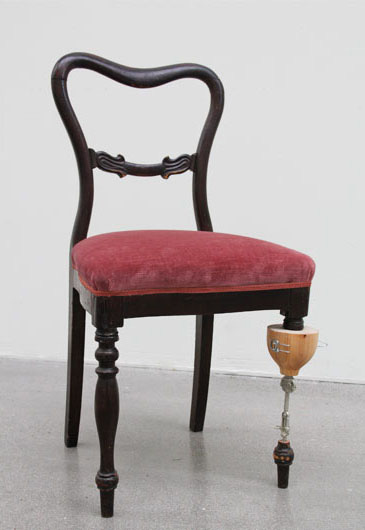

A classic example is the Japanese tea ceremony. Often the items used are quite simple, imperfect, asymmetrical, or even chipped (sometimes deliberately), and yet the objects—especially when considered together—are beautiful. Rather than it being a case of appreciating an object despite its flaws, wabi-sabi embraces those flaws and elevates them to an aesthetic. Those who embrace wabi-sabi can find beauty in the simplest objects, or even in breakage and decay.

My aversion to the clinical rules of modernism led me to embrace this elusive approach. In one sense it’s the antithesis of the conventional approach which seeks to master the object, to impose the artist’s vision from above, to attempt to realize an idea by bending the metal to your will. That approach leaves little room for accident, non-precision, and intuitive action. Wabi-sabi teaches you to embrace what you fear.

Every craftsman knows their limits: the imperfections stare back from the finished piece. In one sense, all things are incomplete, in a never-ending state of becoming or dissolving. Often we designate stages as “finished” or “complete”. The notion of completion has no basis in wabi-sabi.

Rather than polishing a piece until it shines, wabi-sabi teaches you that all objects will decay and tarnish, metal will rust, silver will lose its sheen. Objects record their natural decay from sun, rain, wind, heat, and cold, through staining, warping, shrinking, cracking, and shrivelling. In addition, the history of their use and abuse is recorded in nicks, chips, bruises, scars, dents, and peeling.

Wabi-sabi objects can appear coarse and unrefined, and, on first glance, their craftsmanship may be near-impossible to discern. Indeed, they are supposed to appear coarse and unrefined. Instead of fighting nature’s decay, wabi-sabi embraces it and elevates it to an art-form of unconventional, modest, humble, imperfect, tragic, raw beauty.

Everything falls apart. Everything fades into non-existence eventually. Through the prism of wabi-sabi, I’m trying to capture the moment of decay—freeze-framing the metal just at the point where the rust is beautiful rather than repulsive. I take the clean, pure silver, and I age it, oxidize it, rust it, and beat it to within an inch of its life. Each chip or crack is another invented story, an imagined history, a past-life for the object that never was.